Bright sparks: Part 1

Creativity through neurodiverse wiring

Introduction

Up until just over a decade ago, autism was a word I associated with things removed from my everyday life. Things like movies. You know the ones—Rain Man, maybe a few late-night documentaries. It felt distant, clinical, cinematic. That all changed when my first son, Greg, was two years old and we started to suspect he might be on the spectrum. Suddenly it wasn’t academic (or cinematic) anymore. It was home. Since then, I’ve gone from ad exec to amateur neurologist, decoding everything from sensory processing to speech therapy schedules. And somewhere along the way, I started seeing the ad industry—the one I’d worked in for years—through a completely different lens.

To me, it turned out the creative world has always been a bit of a sanctuary for neurodivergent minds. We just never called it that. We called it "thinking different." We applauded weird ideas, unconventional logic, obsessive attention to detail—and never once stopped to consider that these weren’t quirks, they were clues. Clues that a different kind of mind was at work, often hiding in plain sight, contributing brilliance without ever asking to be accommodated.

Unique cognitive processing

Autism isn’t one thing. It’s not even one set of things. It’s a spectrum, a non-linear constellation of traits that vary wildly from person to person. But one consistent throughline is this: people on the spectrum process the world differently.

There’s often a gap in communication. For some, every sound, light, and motion come through at equal intensity. Imagine trying to hold a conversation while being hit with a sensory tidal wave. That lack of sensory hierarchy isn’t a bug. It’s a feature. It just means their minds are wired to absorb everything. Sometimes, or with some individuals, often in stunning detail.

It’s easy to mistake that for being aloof or disengaged. But what’s really happening is high-volume data intake. In a world obsessed with productivity, this kind of immersive observation is a superpower. Please excuse that overused allegory. The challenge is that our systems—school, work, even play—aren’t built to accommodate or handle it. We praise focused thinking but rarely make space for the kind of focus that diverges from the norm.

Neurodivergent thinking leads to a kind of problem-solving approach that’s systematic, analytical, and gloriously original. Where neurotypical creatives might draw from episodic memory or cultural shorthand (what’s been done, what worked), neurodivergent thinkers deconstruct and rebuild from scratch. It’s not associative. It’s architectural. And it’s incredibly useful.

Creativity and innovation

Years ago, I stumbled across a study that confirmed what I was seeing firsthand. It involved a divergent thinking test using common items. Participants were asked to come up with alternative uses for a paperclip. Neurotypical answers included things like earrings or fishhooks. The neurodivergent group gave answers like a ballast for paper airplanes or chips for underground gambling. These weren’t just clever—they were statistically rare. Less than 5 per cent of participants gave similar answers. Statistically, the answers provided were different, arguably more “creative”.

It’s not that neurodivergent people try harder to be original—they simply start from different assumptions. Most of us solve problems by reaching into the shared bag of cultural references we’ve all grown up with. People on the spectrum often don’t reach for the bag at all. They take the problem apart and look at the pieces. They build new tools. Sometimes they reinvent the wheel. Sometimes, it turns out the wheel didn’t need to be round after all.

The correlation between neurodiversity and creativity is fascinating. Neurodiverse individuals have unique cognitive processing abilities that can lead to novel perspectives and innovative solutions. They are often adept at lateral thinking, which involves approaching problems from new angles and generating creative ideas. Some neurodiverse individuals, particularly those with autism, have heightened abilities in pattern recognition, which can contribute to creative problem-solving. Neurodiverse individuals may have intense focus on specific interests, allowing them to develop deep expertise and innovative ideas in those areas. These different ways that neurodiverse individuals perceive and interact with the world can lead to a broader range of creative ideas and solutions.

In a field like advertising, where we pride ourselves on "originality," this kind of thinking isn’t just refreshing—it’s necessary. Most campaigns are just iterations of old ideas wrapped in new copy. Neurodivergent creatives cut through that cycle. They aren’t referencing the cultural jukebox; they’re composing new songs entirely. And in doing so, they expand the boundaries of what creative even means.

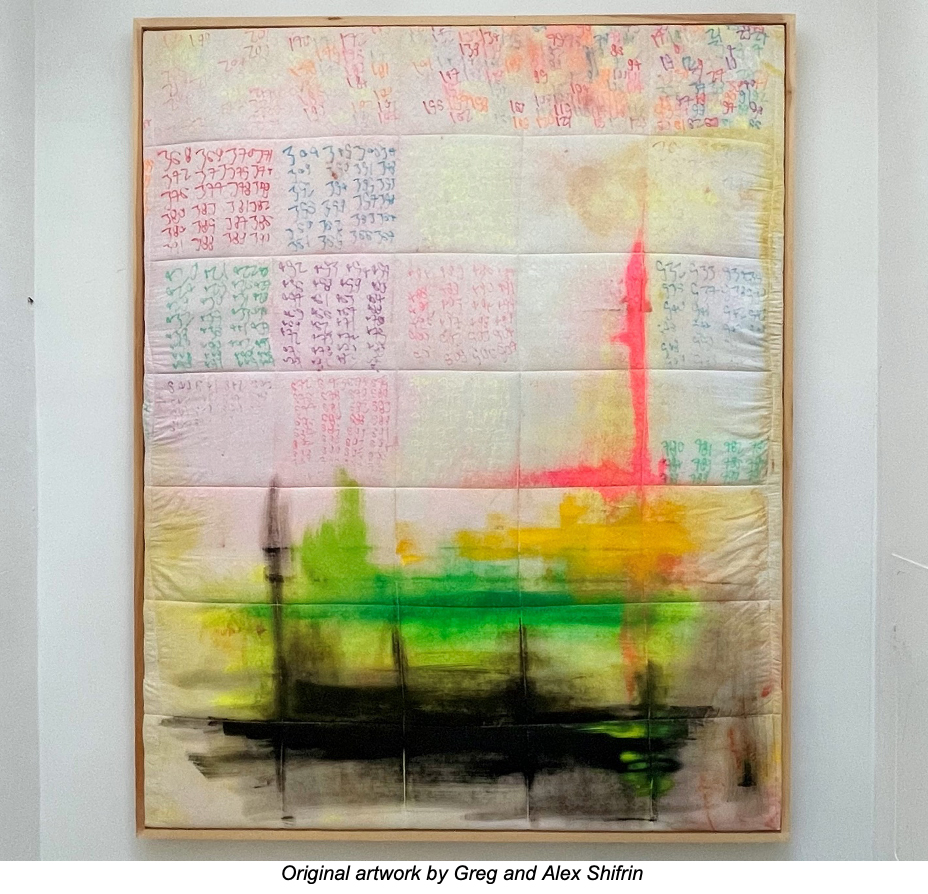

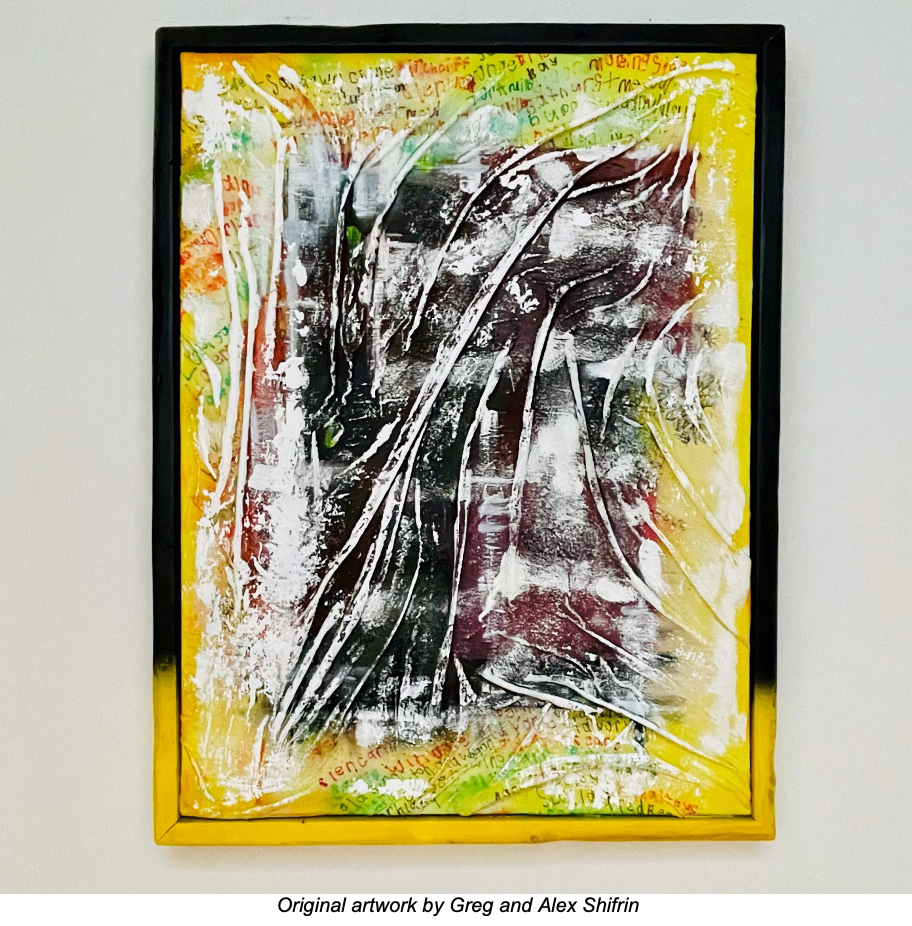

Focused expertise

My son Greg is nonverbal, or was, until recently. He’s started using single words—sometimes with meaning, sometimes not. But what really struck me was his relationship with letters and numbers. No one taught him the alphabet. He just learned it. He started typing full words on my computer before he ever said them out loud. His first written word? "Mama." It’s always mama.

This kind of focused attention—what some call "special interests"—can be dismissed as obsessive. In reality, it’s an engine for mastery. Many neurodivergent individuals go deep into subjects with a commitment most of us can’t fake. Whether it’s mathematics, design systems, historical trivia or computer coding, this kind of hyperfocus is an untapped goldmine in industries that reward depth and nuance.

It’s not just children. I’ve worked with creatives—some openly autistic, others undiagnosed—whose ability to dive deep into research, into typography, into data patterns, was unmatched. Give those individuals a narrow brief and they’ll stretch it across the galaxy.

Inclusion and celebration

Here’s the thing about neurodiversity in the creative industries: we’ve always celebrated it. We just didn’t know it. Take Apple’s iconic “Think Different” campaign. It showcased 18 cultural icons—Einstein, Earhart, Gandhi, Dylan. Of them, 13 are suspected or confirmed to have been on the spectrum. The campaign wasn’t about autism. It was about the power of original thought. But maybe those two things aren’t so different after all.

Inclusion isn’t just about accommodating difference—it’s about understanding where brilliance comes from. Celebrating neurodiversity means not just making space for different thinkers, but recognizing that they’ve always been here, shaping the culture we consume.

We’re not asking workplaces to become therapy centres. We’re asking them to widen the aperture on what leadership, creativity and communication can look like. Often, brilliance is hiding behind behaviours we’ve been taught to correct.

This is where Anne Dean and I really started to align and recognize that our thought process and understanding was something that the creative industry has always known, but not really talked about. People do think differently and when we acknowledge and celebrate those differences, we open up a world of possibility and enable even greater creativity.

Here's Part 2 of this blog series, from Anne Dean, CMA Creativity Council member.